Mastoid Surgery (Combined Approach Tympanoplasty)

How does the ear work?

Sound travels through the outer ear canal down to the eardrum and makes it vibrate. This vibration is transmitted through the three middle ear bones (ossicles) into the inner ear. The vibrations stimulate the nerves in the inner ear, which then pass signals up to the brain where they are interpreted as sounds. The outer ear, the outer ear canal and the outer surface of the eardrum are lined with very thin skin. The middle ear is lined with a mucus-producing membrane and is very similar to the lining of the nose and sinuses or the lungs.

The eustachian tube is the tube at the front of the middle ear which allows air to enter the middle ear to replace what is being used up. If this tube is blocked by inflammation, or infection (which is very common in childhood), it can result either in a build-up of mucus-containing fluid in the middle ear (glue ear), an indrawing of the eardrum (especially the upper part which is a bit thinner) or a combination of the two.

What is the mastoid bone?

The mastoid is the solid lump of bone you can feel just behind the ear. The air space of the middle ear, behind the eardrum, extends backwards into this area of bone. Operations on the middle ear and mastoid are usually performed because of deep-seated infection which will not settle with simple cleaning and antibiotics.

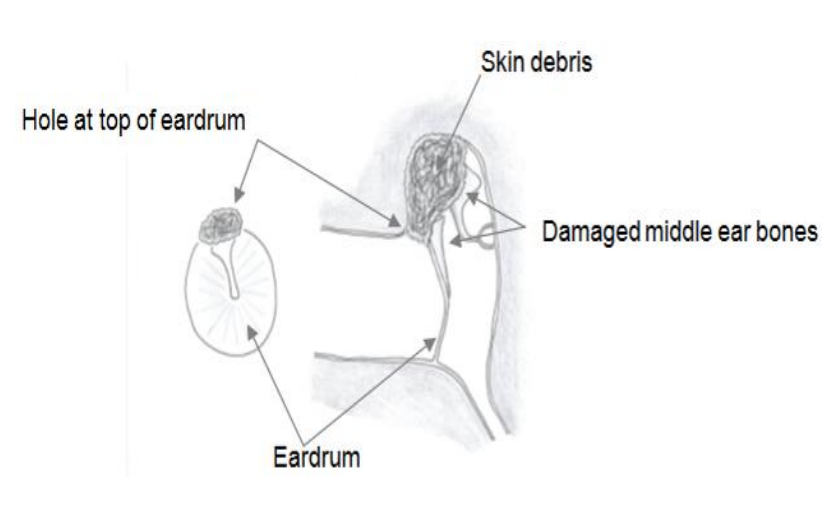

There is an indrawing of the eardrum, usually the upper part, because of a chronic problem with the eustachian tube not working properly. This indrawing turns into a small pocket which is lined with skin, and skin which is being shed gets trapped within this pocket and becomes infected. In other cases, there is skin growing into the middle ear space from the edge of a perforation. More rarely the skin can become trapped in the middle ear after a head injury and a skull fracture.

The ear usually feels wet or actually discharges. The eardrum will be abnormal, with a perforation or an infected pocket, and this will result in a loss of hearing. The bones of the middle ear, which transmit sound into the inner ear, are often involved by the infection and this will result in a greater degree of hearing loss. When we look into the ear in the outpatient clinic we may see the small opening above the eardrum showing signs of infection, but we cannot tell how large the pocket is. A CT scan of the ear will show if there is evidence of bone damage but, as the structures are so small, even the CT scan will not be able to tell for certain how large the pocket of skin is or if the middle ear bones have been damaged.

If the infection is left untreated, the area of infected skin within the mastoid bone will tend to gradually enlarge and may cause complications. The hearing may worsen, there may be dizziness, the nerve that goes to the muscles in the face can be damaged and produce weakness of the face and the infection can spread to the brain. These potentially serious complications are rare, but have to be considered, especially if the ear is left untreated for years.

The main aim of surgery to the mastoid is to make the ear safe by removing the infected tissue. At the end of the operation there will usually be what is called a ‘mastoid cavity’, just above and behind the site of the eardrum which, it is hoped, will line itself with skin and become self-cleansing in the future.

Is there any alternative treatment?

The only way to remove the infection completely is with an operation. In patients who are unfit for surgery, the only alternative is regular cleaning of the ear by an ear specialist and the use of eardrops. This would, at best, only reduce the ear discharge and would not deal with the underlying problem.

How is the operation done?

The operation takes about three hours and is done with a microscope and under a full general anaesthetic. A cut is made in the skin behind the ear. First the surgeon will identify all the disease in your ear. This usually means exploring the ear by a ‘combined approach’ – partly through the ear canal and partly through the mastoid bone behind the ear. Sometimes it is necessary to remove some of the bone of hearing to get all the disease out. Depending on the circumstances, the surgeon may try to immediately reconstruct the hearing bones with a titanium prosthesis, although this may have to be performed in a separate operation later on. The eardrum is reconstructed with cartilage and the ear canal packed with protective dressings.

The skin wound is closed with a dissolving stitch, and a head bandage put on.

It is likely you will be able to go home the same day of the surgery. You can remove the head bandage yourself at home after 24 hours. We will see you in the clinic after two weeks to take the dressings out of your ear canal. We then arrange another appointment for about six weeks later with a hearing test.

After your operation, your hearing will be worse on the side of the operation because of the packing in the ear. You will have some soreness around the ear, especially when chewing. You should keep the ear as dry as possible. Over the next few weeks you will perhaps notice some crackling and popping sounds in the ear as the sponge breaks down and air starts to enter the middle ear again. You will notice some numbness of the back of the top of the ear. This will settle over a number of weeks.

Because of the nature of the operation, it is not usually possible to be sure, in the clinic, whether or not the disease has come back in your ear later on. For this reason, it is usually necessary to undertake a further operation 12 months after the first to check for recurrent disease (this is called a second stage combined approach tympanoplasty). For some people it may be appropriate to have an MRI scan 12 months later as an alternative to surgery. Your surgeon will be able to discuss with you the best option in your circumstances.

What are the possible complications of the operation?

- The operation is done under a general anaesthetic, and all operations under a general anaesthetic carry a small risk. You would be able to discuss this with your anaesthetist

- The nerve which supplies the muscles of the face passes through the middle ear. In amastoid operation there is a small risk of damage to this nerve which may be partial or complete. It may come on immediately after the operation or be delayed by a few days, and recovery can be partial or complete.

- In a small number of patients, the hearing may be further impaired due to damage to the inner ear. If the infection and disease has eroded into the inner ear, there may be total loss of hearing in that ear.

- Sometimes a patient will notice noises in the operated ear (tinnitus), particularly if the hearing worsens on that side

- Dizziness may occur for a few hours after surgery but would rarely be prolonged

- The small nerve which deals with taste from the front of the tongue is on the undersurface of the eardrum and if this is damaged, you may notice an alteration in your sense of taste which usually settles in a few weeks, but can be permanent.

Before the operation

- Arrange for two weeks off work

- Check that you have a friend or relative who can take you home after the operation

- You must not drive for at least 24 hours after a general anaesthetic

- Make sure that you have a supply of simple painkillers at home.

Where can I find out more about the operation?

We would recommend the ENT UK: website www.entuk.org

This has information about mastoid operations.

If you have any questions about general anaesthetics, the Royal College of Anaesthetists website has a lot of information: www.rcoa.ac.uk

Useful contact numbers

Dorset County Hospital Switchboard – 01305 251150

ENT secretaries (Dorchester)

Mr Ford 01305 255138

Mr Tsirves 01305 253167

Mr De Zoysa 01305 255138

Mr Sim 01305 254205

Mr Lale 01305 255510

Mr Kenway 01305 255138

Mr Chatzimichalis 01305 255510

ENT secretaries (Yeovil)

01935 384210

About this leaflet

Author: Mr Glen Ford, ENT Consultant

Reviewed by: Mr Bruno Kenway, ENT Consultant, March 2020

Approved: August 2020

Review date: August 2023

Edition: 2

If you have feedback regarding the accuracy of the information contained in this leaflet, or if you would like a list of references used to develop this leaflet, please email patientinformation.leaflets@dchft.nhs.uk

Print leaflet